I can barely hear my car’s radio over the storm. It’s just a low buzz and a series of rhythmic thumps. I’m alone on the highway, flanked by rows of Nebraskan corn, driving in the shadow of the wind turbines in the distance, steadily spinning along in the rain. Dozens of wind turbines… or hundreds of them. Thousands maybe? They seem to stretch forever–or for at least as long as this awkward conversation with my father does.

Three Fourths Home is a short piece of interactive fiction that captures the feeling of late-night driving and millennial uncertainty. You play as Kelly Meyers, a 20-something who recently moved back in with her folks and who can’t see a path forward for her or her troubled family. As the player, you’re more concerned with the family’s past: Across a main story, an epilogue, and a collection of interesting bonus content, you piece together (and even decide) who these people are and what happened to them.

Like all stressful conversations, there’s no walking away from this one. You have to push through it.

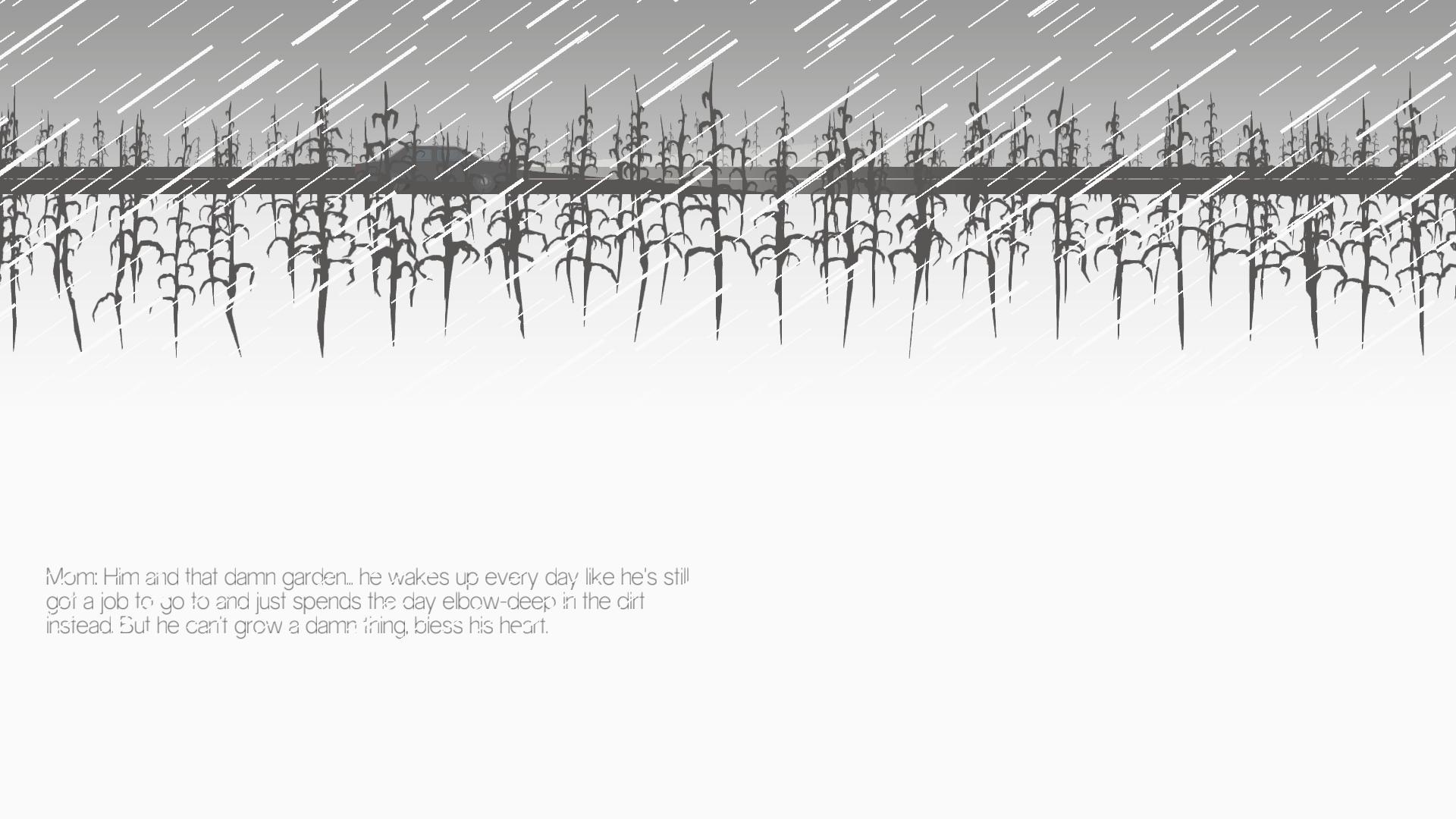

In the game’s main story, you spend about an hour driving through an intense storm while talking with your family members on the phone. On a screen of stark (and occasionally overwhelming) black, white, and gray, you pass through rural Nebraska while choosing dialogue options and taking in the scenery. You hold down the D key to drive forward while selecting dialogue with the up and down arrows. With a press of the F key, the camera zooms in to the silhouette of your car, and your speed shakes the screen. You can mess with your tape deck or flick your headlights on and off, but these mostly serve to occupy your hands (and take up your nervous energy). If it all sounds simple, it’s because it is. But it’s also effective.

Three Fourths Home again proves that interactive fiction can feel urgent, and it’s a reminder that game makers working in the genre have more tools at their disposal than just their words. The droning ambient sounds and the high-contrast zine aesthetic create a tense atmosphere, and the game’s control scheme supports this. In order to progress through conversations you need to continue to drive forward. The second you let go of that D key, everything decelerates into slow motion–the rain, the windmills, the bird that flies overhead–and your dialogue options vanish. Like all stressful conversations, there’s no walking away from this one. You have to push through it, and you must do so with care: It’s all too easy to choose the default response during conversation when you mean only to forward a conversation, due to the game’s measured reveal of possible replies.

The droning ambient sounds and the high-contrast zine aesthetic create a tense atmosphere.

Of course, writer Zach Sanford’s words contribute to the tension, too. Though much of the dialogue is humorous, the conversations you have with Kelly’s mother, father, and brother always work their way back around to some recent trauma–yours or theirs. Games have a history of mishandling the traumatic, but Sanford manages to explore these ideas with restraint and insight. His natural writing sets Three Fourths Home apart from many other games which render personal suffering cartoonish. The Meyers, like real people, are careful but flawed. They know that there are topics you can only really talk about when you can look someone in the eye. But they can’t quite manage their desires to talk about the tough stuff. So they hint at their pasts, talk around their personal tragedies, and occasionally brush close to their painful memories.

The game’s epilogue subverts this structure. Still playing as Kelly, you are taken back into her memory of a time months before the main game’s story. But unlike a linear flashback, this is memory reflects the doubt and regret that often comes with hindsight. You can choose to make the same dialogue choices that Kelly made all those months ago, or you can linger on the “what ifs.” What if she had told her mother about her problems? What if she’d worked harder in school? What if she’d taken a different bus that day? You’re not actually seeing alternate outcomes–you’re just obsessing over them the way we all do.

The conversations you have with Kelly’s mother, father, and brother always work their way back around to some recent trauma–yours or theirs.

The extras included in Three Fourths Home build on this. On top of being able to listen to the game’s soundtrack, you’re able to flip through one of Kelly’s college photography projects and read a collection of her brother’s short stories. The photos are flawed and the fiction flirts with cliché, but both are better for it. Central to Three Fourths Home is the notion that creative work helps us work through our trauma, and being able to see the art these characters made sells that. Since so much of Three Fourths Home is about understanding who these people are, this stuff isn’t superficial bonus content. It’s a true part of the experience.

In total, that whole experience only took about two hours of my day. But it left me winded. There is a real velocity to Three Fourths Home. It sneaks up on you, quietly at first, before suddenly becoming overwhelming. Its closest analogs aren’t other games, but works like John Darnielle’s novel Wolf in White Van or the haunting music of lo-fi artist Mount Eerie–art that rumbles and groans and then springs into action.

More than anything, though, Three Fourths Home reminded me of one of those nights where you look down to see that you’re going ten… twenty… thirty miles over the speed limit. But you just can’t bring yourself to lift your foot off the gas pedal. You’ve got somewhere to be.

Powered by WPeMatico