He agreed that it was time. He was infected. It was more than the Zed curse. We all had that–we knew that we were ticking zombie time bombs. He was sick, and he was going to die, but he couldn’t do it at our new home. We couldn’t risk it; we’d sacrificed so much to get there. We drove to a home in what had been the pristine town of Marshall. How many suburban daydreams had died since the outbreak? He could die with dignity here. But when we arrived at the home, he fled. I chased him in his aimless sprint across the decaying but once vibrant Trumbull Valley–killing hordes of zombies to protect him–until, twenty minutes later, I realized that I’d encountered another of State of Decay’s game-breaking bugs, and I had to reload my save and start anew.

Whenever I attempt to describe State of Decay to people who have never played the game, I find myself describing the game I want State of Decay to be–and the game that Undead Labs attempted to craft–more than the game that State of Decay actually is. State of Decay wants to be many games–chief among them the first video game to properly capture the community survival elements of a Dawn of the Dead film in mechanical terms (as opposed to the narrative terms of Telltale’s The Walking Dead)–and, at its best moments, it creates a sense of community, tension, and character agency matched by few of its peers. But for each moment of spontaneous, unscripted story wonder that State of Decay generates, it is also one glitch, bug, or broken feature away from drawing you completely out of its experience.

Intelligent play is not nearly as interesting as life on the edge of total annihilation.

State of Decay: Year-One Survival Edition collects the base State of Decay game from 2013 as well as its two major add-ons (the infinite sandbox Breakdown and the story-driven Lifeline), and updates it for the Xbox One and PC (for those who didn’t already own the game for the latter). Set in an unspecified portion of the United States, State of Decay tasks you with ensuring the survival of an ever-growing (or shrinking, depending on your competency of play) community after a zombie apocalypse consumes the world. You gather resources, explore, and fight (but mostly avoid) the undead as you look to stay alive.

State of Decay feels like a collection of other games’ remnants in part because its various systems are separate and distinct entities that often fail to complement each other in meaningful ways. Though the initial hours of the game may give the impression that State of Decay is a punishing and clunky exploration-focused action-adventure game as you complete the scripted prologue and the early (but still heavily scripted) hours of more freeform play, its primary focus is on building and maintaining your community of survivors.

Beyond a handful of plot-mandated characters–who can all meet permanent death if you fall to one of the game’s many ways to die–you collect a procedurally generated group of survivors that you both control directly and observe as they integrate into their new home. Whether it’s the cramped confines of the Spencer’s Mill church, where the game proper begins, or one of the more spacious shelters that you can find throughout State of Decay’s massive world, you use these survivors to explore towns and the wilderness to look for supplies–food, bullets, guns, medicine, construction materials–to ensure the survival of your home as well as to complete the missions that rocket State of Decay toward its (literal) explosive end.

Sit still–I’m not done with this haircut yet!

You may come to rely heavily on the first two characters you find in State of Decay–the tough but lovable Marcus and the guarded but bad-ass Maya–but it’s the procedurally generated characters and their interactions with the established voices in your group that craft many of the game’s most interesting stories and help to provide a distinct sense of personality to each playthrough. Eventually, however, the core gameplay loop starts to feel monotonous and tired, which sets in the second your shelters begin to develop any sense of consistent security and prosperity.

One of my procedurally generated heroines joined the group and didn’t want to get to know or talk to anyone beyond Marcus, who had rescued her from a horde when she’d gone out on one of her first supply runs. But, when I played her on a sprint (once again literal, as I’d accidentally run into another horde) focused just on acquiring food and construction materials from nearby buildings in Marshall, our resident “voice on the radio”–the lupus-infected Lily–called me and asked if I’d pick up a keepsake from her deceased father. My heroine had no reason to help Lily, but I did it–and nearly died–and finally, this girl who had felt like a collection of statistics began to feel like she belonged in the group. And, from then on, she became an integral part of my character rotation.

Your play is as much defined by who dies as it is by who lives and contributes the most to the success of your group. Beyond two members of my party who died of a story-mandated plague, I only lost one other member of my State of Decay family. I’d sent one of my original survivors from the church out to meet with the Wilkersons–a family of gun-running thugs whom I decided to placate rather than confront–but she never made it that far. On her drive to their farmhouse, I noticed a supply drop in a huge corn field and investigated. I should have known better. I’d nearly died opening one earlier in the game. The supply drop was a hotbed of zombie activity, and before I could run back to my truck, a Feral–the most aggravatingly agile and swift type of zombie–grabbed her, and, by the time I had pushed him away, a sea of zombies had her surrounded on all sides. She was ripped into gory halves.

State of Decay is always one glitch, bug, or broken feature away from drawing you completely out of its experience.

The endgame supports a solid strategy of turtling and building up defenses, meaning that you rarely feel the sting of encroaching starvation or the fear that your ammo supply has run dry. Otherwise, State of Decay’s choices and consequences are only tangentially related to the main plot. Every resource you use is gone forever and a choice you won’t have again down the road, and State of Decay never lets you forget it. The fear that a beloved and effective melee weapon will suddenly break is always there. If you play well enough to lead your survivors to a degree of comfort and security, you feel that you earned it through judicious planning and execution, although you miss those sweat-inducing early runs in the game where failure and retreat meant that some survivors wouldn’t eat that day. It all becomes too routine if you play well enough; Intelligent play is not nearly as interesting as life on the edge of total annihilation.

By the endgame, you have enough resources to not have to worry about the supply runs that are the key to success in the early game, beyond finding relatively common construction materials, which remain key throughout the gam. You are also provided enough human capital to eliminate most of the challenge of avoiding the great masses of zombies that the game intentionally designed to kill you swiftly if you engage too many at once. “Influence” is the game’s key currency, which you gain for completing missions and runs, and you can use it to ask other members of your community for help–a good design and essential for clearing out packed infestations–as well as to call for backup from survivors in Trumbull Valley who aren’t part of your group. This is problematic when you can call in three magical SWAT team members for a barely nominal influence fee who can then shotgun-blast all the zombies swarming that hard-to-reach supply drop. The cooldowns on those abilities keep you from spamming them, but if you save them for major missions, they remove every last ounce of challenge from the game.

Despite that, the character-generated stories in State of Decay–leaving Spencer’s Mill for fear of the military only to become close allies with them in a well-planned twist and realizing the final cost of my appeasement of the Wilkersons–are so fascinating and well crafted that the game’s failures in virtually every other category become all the more agonizing. Year-One Survival Edition has addressed few, if any, of the bugs, glitches, and basic structural flaws at the heart of the base game. Environmental clipping is constant throughout the game. Zombies often wander halfway through walls and doors. Textures don’t so much pop in as entire structures and characters appear out of nowhere, including one instance where I killed an invisible zombie that was terrorizing my group. The AI of your fellow survivors ranges from “at least they aren’t getting themselves killed” to “where the hell are they going, and why won’t they stop?”

The character-generated stories are so fascinating and well crafted that the game’s failures in virtually every other category become all the more agonizing.

It isn’t quite right to say that the cars in the game control like boats. At least boats in the water have some degree of mobility and precision. The cars in State of Decay control like boats on land. The game intentionally makes melee combat against more than two or three zombies at once difficult both to sell how vulnerable your character is and to teach you to avoid being swarmed, but combat in any sense in State of Decay also reminds you that your character barely controls better than your vehicles, and it’s too easy to get caught in the environment or behind AI characters that don’t know how to get out of the way and then find a valuable member of your party killed for good. As for inventory management, I appreciate the notion that there’s only so much stuff a person can carry at once, but the lack of an ability to give your squadmates equipment and items, and the menu-heavy nature of organizing your supplies, constantly draws you out of suffocating survivalist atmosphere and reminds you that you’re playing a game.

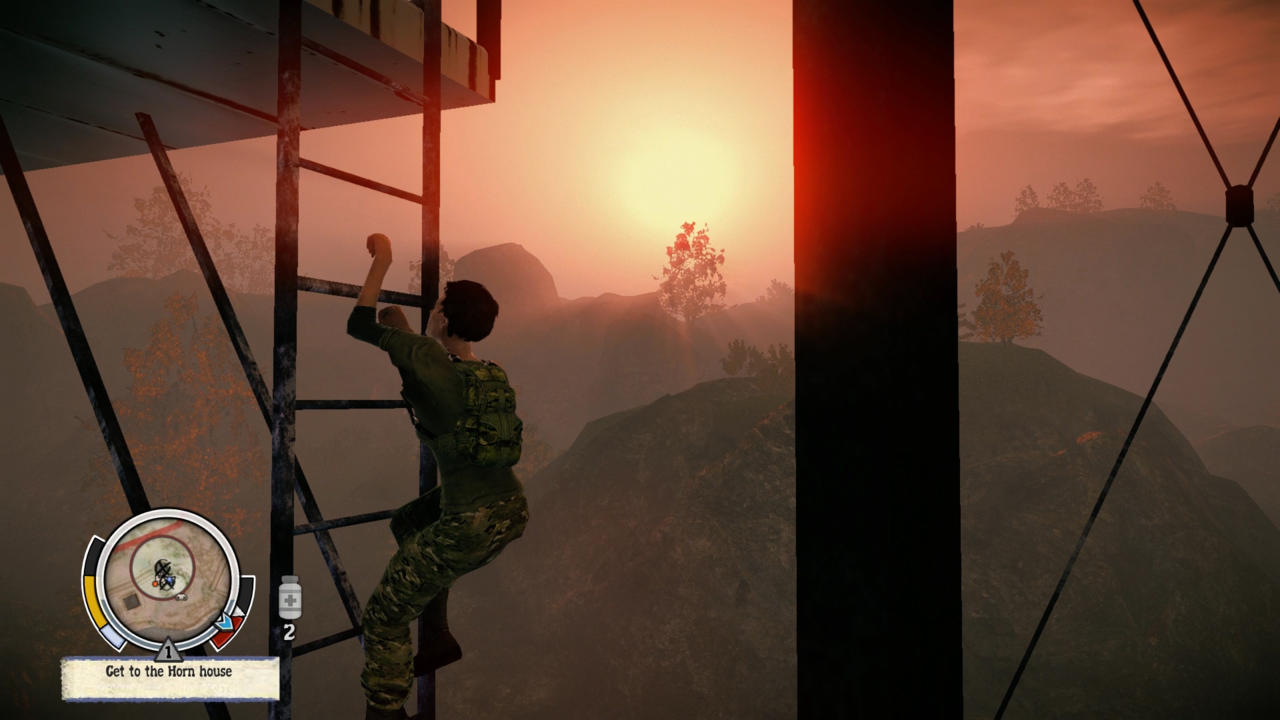

Trumbull Valley itself never feels like a place that would actually exist. It comes off as a bizarre hybrid of the American Southwest with its rocky orange protuberances dotting the landscape fused with World of Warcraft‘s Westfall, with tiny farmsteads and towns propped up with cornfields elsewhere. State of Decay’s total lack of aesthetic cohesion is never charming in an ironically intentional sense; instead, it constantly reminds you that you’re playing a game that could be so much better.

If I found myself describing the game to friends as the game I wanted it to be more than the game it was, it’s because the “ideal” version of State of Decay is intoxicating. When State of Decay was fashioning stories around my crew and the decisions I made–or failed to make by taking too much time to act and costing the lives of people not in my direct group–it spoke to a world that existed both around the choices I made and beyond anything my individual play shaped. But State of Decay was too willing time and time again to remind me not only of its inherent gaminess, but also that large swaths of that game were outright broken.

Powered by WPeMatico