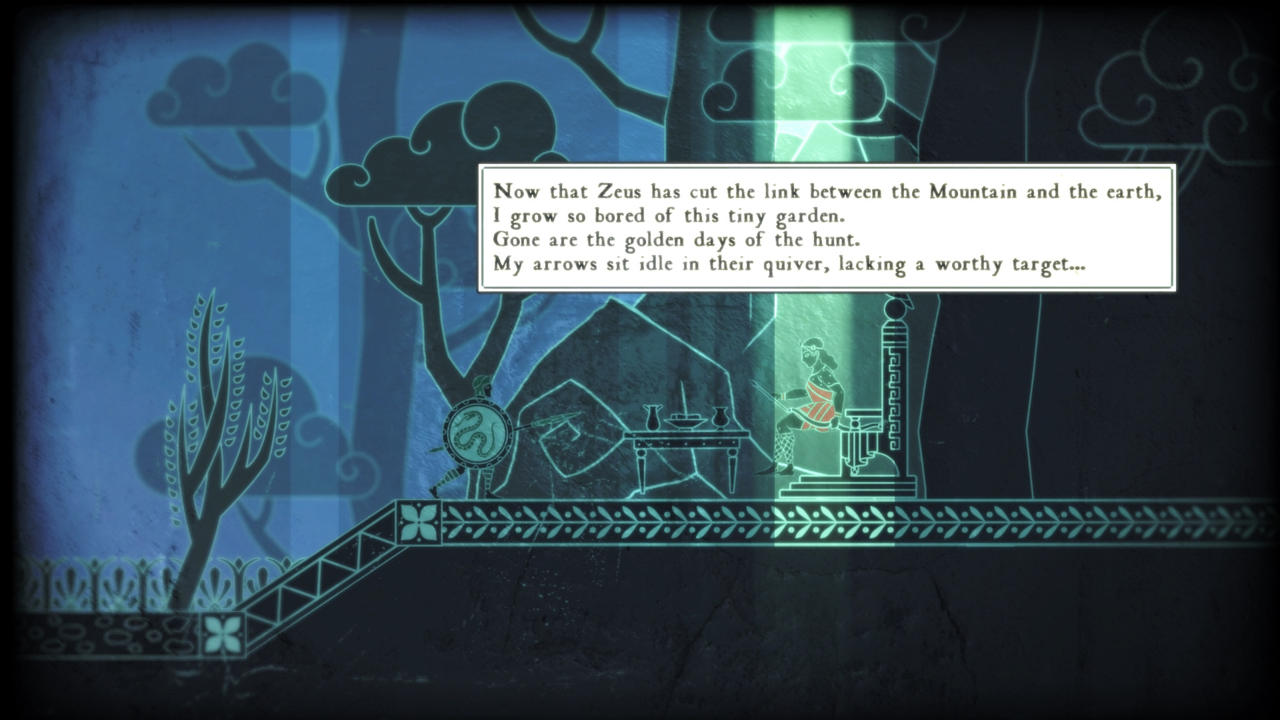

Playing Apotheon is like being an archaeologist exploring and unearthing the mysteries of an unknown world. You find your hands stretching thousands of years back in time to discover a story you didn’t know had unfolded. The art is immediately distinctive. While the same could be said for a fair number of independent games, this time it’s more than just a pretty background. Like the ochre-stained walls of an Athenian temple circa 500 BC, Apotheon’s characters are little more than black silhouettes. The environments are elaborate, sprawling, two-dimensional cutaways. They beg you to imagine this wondrous world in its full glory, but they resist conventional beauty.

These paintings are all we have left. Beneath that veneer is a run-of-the-mill action platformer. You make a few jumps here, and fight a few baddies there. Throughout, the minute-to-minute play stays simple. You grab weapons and shields lying around, using one button to attack, one to block, one to jump, and the two sticks to move about and aim your strikes with added precision. There’s a basic crafting system as well, but it’s a straightforward one. Instead, Apotheon expounds on these basic ideas with a string of apropos twists. When venturing into the underworld, for example, you often have to give up the use of a shield to navigate by torchlight, unless you’ve found a shield kept by the servants of the sun god, Apollo, that can light your path. Each area has something unique to uncover that make some parts of your journey harder, others easier. Such flourishes greatly add to Apotheon’s character, and support the game’s mythological inspirations.

Our hero in this neo-Classical myth is Nikandreos. While not a member of the traditional Greek pantheon, his epic sticks to the conventions of Classical tragedy. In the prelude, his hometown, Dion, is out of favor with the gods. The forests have no game, the fields yield no crops, and the sky is stuck in perpetual twilight. Nikandreos, seeking to restore the mantle of humanity, journeys to Mt. Olympus, the realm of the deities. There he learns that Zeus, king of the gods, has grown to hate people and will not rest until they are destroyed.

If that sounds clichéd, that’s because, from a modern lens, it is. Apotheon eschews modern expectations, reflecting a far older brand of storytelling. Greek tragedy, and Greek heroes in particular, are far different from the super-powered defenders of good we see today. Greek heroes were flawed, difficult people who accomplished great things, though were often cruel and awful as well. Classical tragedy is even more unusual. These stories draw on themes such as the conflict between men and gods, and depict arrogant heroes that unravel themselves with acts of great hubris.

The ancients were a scared, superstitious people. We frequently forget their struggles, remembering them instead as creators of grand, monolithic civilizations. We forget these people believed not only in divine providence, but also in retribution. We forget the limits of their understanding, and that for these classic civilizations catastrophe was evidence of the wrath of the gods. From that perspective, Apotheon is hauntingly poignant.

In his quest for salvation, Nikandreos partners with Hera, queen of the gods. She’s been brewing over her husband’s many affairs and now lusts for justice. She guides Nikandreos, pointing out to him the weaknesses of the mighty Olympians. At every turn, figures from Greek myth appear–each with their own grudges, their own motives–to help Nikandreos. As he gathers power, he leaves nothing but death and destruction in his wake. Between each act, he sees that his people are suffering and dying–punished for his own arrogance. However, he, or rather we, never once waver. On we march to claim our prize, and to topple the gods.

This drama works because it’s relatable. At some point, every person who has ever lived has experienced pain. Suffering is a fundamental human experience. When we’re at our worst, we seek relief, no matter how destructive it may prove to be. The gods aren’t much different. Hera is driven by her lust for revenge, Zeus by his disappointment in his people. The other gods and goddesses you meet have their own motives, their own goals, and a slew of victims that want you to succeed. You become the vessel for hope, relief, and peace, your only failure being that you’re so damned foolhardy that you can’t see the consequences of your actions.

Apotheon shares many of its narrative threads with God of War, but the differences pile up quickly. Where God of War sticks to video game tropes, Apotheon is content to ground itself in myth. This is a fantastical world where gods and goddesses roam the earth, but beyond that, there’s no need for the suspension of disbelief. Where God of War is flashy and bombastic, Apotheon is soft and personal. Every battle is slow and careful. Each hit is quite damaging, so you hold your shield up and bide your time for a perfect strike.

Apotheon eschews modern expectations, reflecting a far older brand of storytelling.

Your weapons and shields also have limited durability. At best, a spear lasts you a few small battles. There are no flaming chain blades here. Instead, you have a small assortment of conventional blades, axes, and pikes. Shields can cover only a limited part of your body so you also have to predict the direction of incoming strikes. It’s similar to a two-dimensional Dark Souls in that respect. Unfortunately, that lack of depth is one of the few knocks against Apotheon. Repeating the block-wait-attack tactic for ten hours gets thin. The only respite is the bouts with the gods themselves.

Each deity has an individual domain with its own rules and challenges. Artemis, the goddess of the hunt, for example, transmutes you into a deer and try to lay traps to kill you. To best Athena, goddess of wisdom, you must navigate three concentric, rotating labyrinths. These contests serve two purposes. They reinforce your smallness and their godhood, and add variety to an otherwise monotonous trek.

My time with Apotheon reminded me of a conversation from the film Prometheus. David, an android, discusses with Charlie, a human, the relationship of creators and creation. David asks Charlie why people created robots. The response, “We made you because we could,” upsets David. “Can you imagine how disappointing it would be for you to hear the same thing from your creator?”

Apotheon asks these same kinds of questions. Zeus, consumed with regret for how petty mankind has become, wants to unmake us. Nikandreos, having observed the same pettiness in other Olympian gods, conquers them and creates a new world where he is god. The names Apotheon and Nikandreos both allude to this chain of events, meaning “one who is elevated to godhood” and “victorious man,” respectively. Victory, and even deification then, are fated from the beginning. You will win. You are the hero, after all, but I can only wonder if in time his creation will bring him relief or despair.

Powered by WPeMatico